In the early noughties, two books were published on corruption within the ranks of London’s Metropolitan Police in the 1990s. The first was Bent Coppers by the BBC Journalist Graeme McLagan, the second was Untouchablesby two former Guardian journalists, Michael Gillard and Laurie Flynn. The two titles covered the same territory, the same allegations, the same cases; they both agreed that there had been corruption within the ranks of the Metropolitan Police. But there the similarity ended, the two reaching starkly different conclusions. Whereas Bent Coppers saw the Met’s attempts to stamp out corruption as largely successful and was in general admiring of the secret unit set up to root out the bent cops, Untouchables was far more critical, arguing the anti-corruption crusade was itself corrupt, guilty of ineptitude when confronting those officers who were truly guilty while hounding innocents from the ranks.

Whatever the truth of the Met’s success in tackling police corruption in the 1990’s, the extent of such corruption is often hotly debated. The Met and other UK police forces often cite rotten apples: lone officers falling for temptation, the rest of the force being honest. Their differences aside, both Bent Coppers and Untouchables argued that it was worse than this, that while corruption was still a minority, it amounted to rotten barrels rather than individual apples. Even so, few would argue that the police haven’t cleaned up their act since the bad old days of the 1970’s and 80’s. Television series, such as Life on Mars and Ashes to Ashes,have popularised the view that the police back then were knuckle-dragging racists and misanthropes, who all too often pocketed a bribe.

The belief that the police had a serious corruption problem in years gone by is well founded. In 1969, The Times published an account of detectives taking bribes that led to three officers jailed in 1972. Later in the decade, the Clubs and Vice Unit was found to be seriously on the take, with DCS Bill Moody most famously convicted. Finally, there was Operation Countryman, a widescale investigation into allegations of corruption in the City of London force, an investigation that soon widened to the Met as well. It’s difficult to underestimate the impact of Countryman. The investigation, which petered out in ignominious failure, polarises people to this day. Some believe there was little corruption to start with, that by then the Met had cleaned up its act and recovered from the scandals of before. Others see an establishment coverup, one that pre-empts alleged cover-ups to follow.

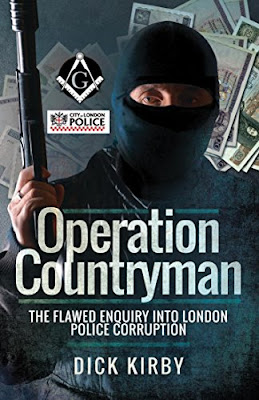

Operation Countrymanby Dick Kirby is the first, and probably last, book to examine Countryman. This is for two reasons: firstly, the Countryman report has never been published, has in fact been buried in the National Archives, while secondly, many of the original participants have passed away. Kirby, himself a former Met detective, has pulled out all the stops, used all his contacts, to speak to as many people as he can from the period. The result is a unique and outstanding work of scholarship, albeit one that is far from perfect.

Kirby is clearly of the school of thought that Operation Countryman was an inept and largely pointless exercise, characterised by much incompetence and not a little vindictiveness. In fact, the thrust of his book is very similar to the conclusions Gillard and Flynn reach in Untouchables regarding efforts to tackle corruption in the nineties. Namely, that the anti-corruption investigations were themselves fatally flawed. But whereas the efforts to target corruption in the Met in the 1990’s were internal, Countryman was run by an external force, namely Dorset Police. Why a rural force with comparatively little serious crime was chosen, rather than one of the big metropolitan forces such as Liverpool or Birmingham, is a mystery Kirby cannot solve; like others then and since he is left scratching his head with disbelief. One revelation to come from this title is that many of the Dorset officers assigned to Countryman were traffic cops, promoted and given the title “detective” purely for the investigation. Was it any wonder that they floundered? Many of the allegations of corruption came from career criminals and the Countryman team soon ran into trouble offering them immunity for their crimes in return for testimony. This again is prescient of conclusions reached by Untouchables, that the 1990’s investigation was too gullible and was led astray by those it tried to cultivate in the criminal underworld.

But there are serious deficiencies in Kirby’s work. The biggest is his tone. Whereas Gillard and Flynn, as serious and professional journalists, marshalled their evidence and set out their conclusions with a devastating conciseness, Kirby sets out his stall early on with partiality that often borders on sneering. This is an author steeped in history as a former Met Flying Squad officer, who appears to take the Operation Countryman inquiries undoubted failings personally. To be clear, this is not to say that Kirby isn’t right. He’s done his research, he’s spoken to many people. His conclusions about Countryman might well be correct. But it’s difficult to judge this from the narrative because the tone of the book comes across as biased, whether or not it in fact is.

Unlike Bent Coppers and Untouchables, books written about corruption in the Met in the 1990s, both of which accept that there was a corruption problem (though how serious it was is still a matter of debate), Kirby believes there was no corruption uncovered within the Met by Countryman. Rather, what corruption discovered was confined to the City force. Furthermore, he convincingly argues that justice here owes more to an honest City detective, John Simmonds, than to Countryman. This last point is almost certainly true, (other books which touch on Countryman have concluded similar, not least Craft and Crime by Mike Nevile). But was there really no corruption uncovered in the Met? When corruption reared its ugly head in the sixties and seventies, then later in the nineties (albeit, almost certainly to a lesser degree) it seems difficult to believe.

Here, again, we come back to the tone of Operation Countryman. Reading this title, one can’t help but be hugely impressed by the research the author has conducted, the people he has spoken to and the facts he has marshalled. The apparent bias and the sneering disdain he holds for the Countryman team however fatally undermine his case and lead the reader to wonder whether, unconsciously perhaps, he discounted findings that did not fit his case. Another possibility is that people who held views diametrically opposed to his conclusions refused to speak to him. To be sure, this is all speculation; it might well be that his arguments are sound. In which case, he would have been better served by holding back and letting the facts speak for themselves.

To be sure, Operation Countryman is well worth a read, and as likely the only title to be published on the scandal, a worthy addition to the scholarship of police corruption in the UK context. That said, the author can’t help but wander into polemic and this only weakens his arguments.